| [Top][Contents][Index] |

LilyPond – Aufsatz über den automatischen Musiksatz

|

Dieser Aufsatz diskutiert den automatischen Musiksatz von LilyPond Version 2.25.16. |

| 1 Notensatz | ||

| 2 Literatur | ||

| Appendix A GNU Free Documentation License | Die Lizenz dieses Dokuments. | |

| Appendix B LilyPond-Index |

|

Zu mehr Information, wie dieses Handbuch unter den anderen Handbüchern positioniert, oder um dieses Handbuch in einem anderen Format zu lesen, besuchen Sie bitte Handbücher. Wenn Ihnen Handbücher fehlen, finden Sie die gesamte Dokumentation unter https://lilypond.org/. |

| [ << Top ] | [Top][Contents][Index] | [ Literatur >> ] |

| [ < Top ] | [ Up : Top ] | [ Die Geschichte von LilyPond > ] |

1 Notensatz

Dieser Aufsatz beschreibt, wie LilyPond entstand und wie es benutzt werden kann, um schönen Notensatz zu erstellen.

| 1.1 Die Geschichte von LilyPond | ||

| 1.2 Details des Notensetzens | ||

| 1.3 Automatisierter Notensatz | ||

| 1.4 Ein Programm bauen | ||

| 1.5 LilyPond die Arbeit überlassen | ||

| 1.6 Notensatzbeispiele (BWV 861) |

| [ << Notensatz ] | [Top][Contents][Index] | [ Literatur >> ] |

| [ < Notensatz ] | [ Up : Notensatz ] | [ Details des Notensetzens > ] |

1.1 Die Geschichte von LilyPond

Lange bevor LilyPond benutzt werden konnte, um wunderschöne Aufführungspartituren zu setzen, bevor es in der Lage war, Noten für einen Unversitätskurs oder wenigstens eine einfache Melodie zu setzen, bevor es eine Gemeinschaft von Benutzern rund um die Welt oder wenigstens einen Aufsatz über den Notensatz gab, begann LilyPond mit einer Frage:

Warum schaffen es die meisten computergesetzten Noten nicht, die Schönheit und Ausgeglichenheit von handgestochenem Notensatz aufzuweisen?

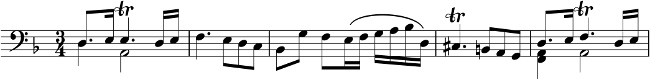

Einige der Antworten können gefunden werden, indem wir uns die beiden folgenden Noten zur Analyse vornehmen. Das erste Beispiel ist ein schöner handgestochener Notensatz von 1950, das zweite Beispiel eine moderne, computergesetzte Edition.

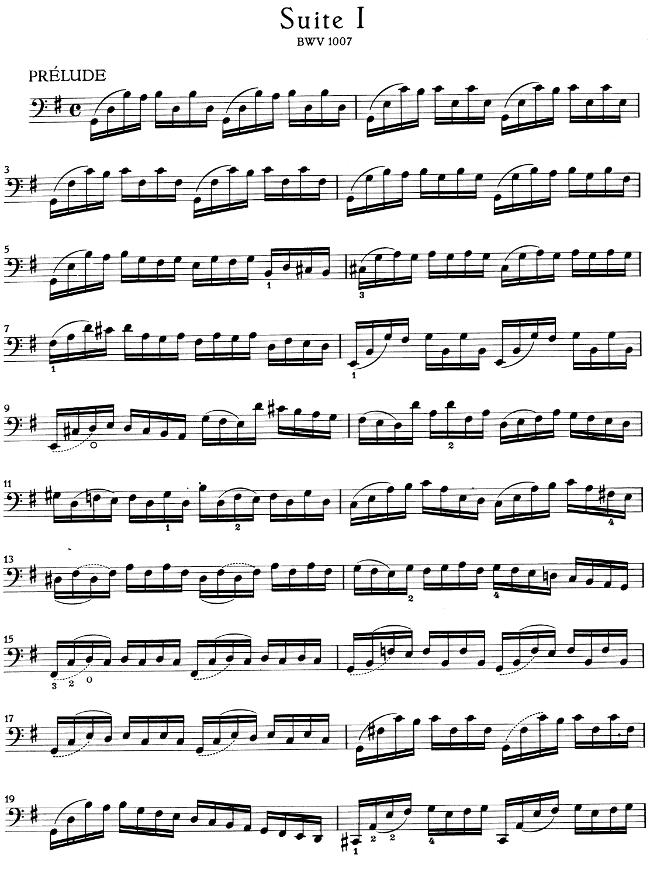

Bärenreiter BA 320, ©1950:

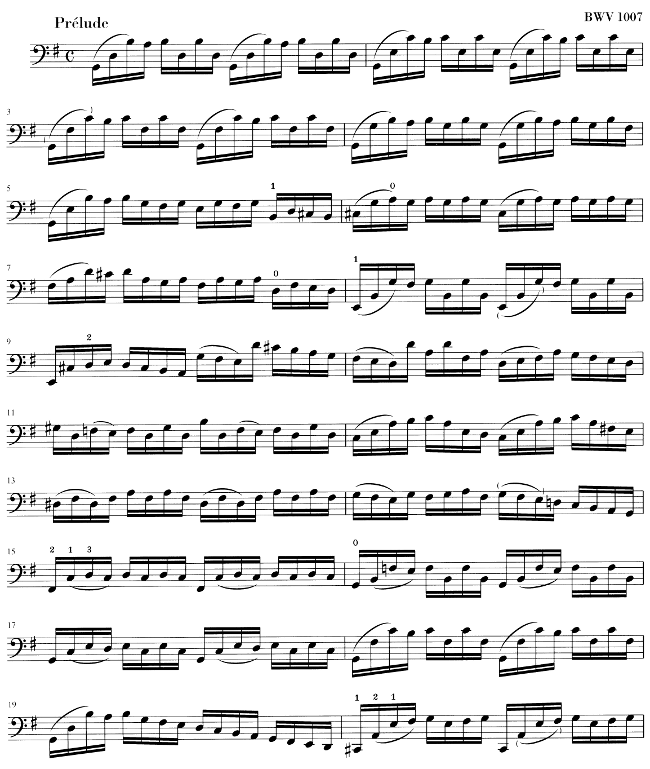

Henle Nr. 666, ©2000:

Die Noten sind identisch und stammen aus der ersten Solosuite für Violoncello von J. S. Bach, aber ihre Erscheinung ist sehr unterschiedlich, insbesondere wenn man sie ausdruckt und aus einigem Abstand betrachtet. (Die PDF-Version dieses Handbuchs hat hochauflösende Abbildungen, die sich zum Drucken eignen.) Versuchen Sie, beide Beispiele zu lesen oder von ihnen zu spielen, und Sie werden feststellen, dass der handgestochene Satz sich angenehmer benutzen lässt. Er weist fließende Linien und Bewegung auf und fühlt sich wie ein lebendes, atmendes Stück Musik an, während die neuere Edition kalt und mechanisch erscheint.

Es ist schwer, sofort die Unterschiede zur neueren Edition auszumachen. Alles sieht sauber und fein aus, möglicherweise sogar „besser“, weil es eher computerkonform und einheitlich wirkt. Das hat uns tatsächlich für eine ganze Weile beschäftigt. Wir wollten die Computernotation verbessern, aber wir mussten erst verstehen, was eigentlich falsch mit ihr war.

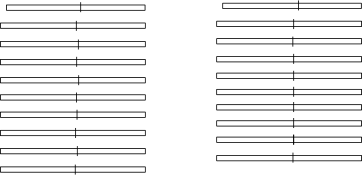

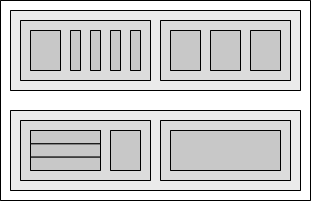

Die Antwort findet sich in der präzisen, mathematischen Gleichheit der neueren Edition. Suchen Sie die Taktstriche in der Mitte jeder Zeile: im handgestochenen Satz hat die Position dieser Taktstriche sozusagen natürliche Variation, während die neuere Version sie fast immer perfekt in die Mitte setzt. Das zeigen diese vereinfachten Diagramme des Seitenlayouts vom handgestochenen (links) und Computersatz (rechts):

Im Computersatz sind sogar die einzelnen Notenköpfe vertikal aneinander ausgerichtet, was dazu führt, dass die Melodie hinter einem starren Gitter aus musikalischen Zeichen verschwindet.

Es gibt noch weitere Unterschiede: in der handgestochenen Version sind die vertikalen Linien stärker, die Bögen liegen dichter an den Notenköpfen und es gibt mehr Abweichungen in der Steigung der Balken. Auch wenn derartige Details als Haarspalterei erscheinen, haben wir trotzdem als Ergebnis einen Satz, der einfacher zu lesen ist. In der Computerausgabe ist jede Zeile fast identisch mit den anderen und wenn der Musiker für einen Moment weg schaut, wird er die Orientierung auf der Seite verlieren.

LilyPond wurde geschaffen, um die Probleme zu lösen, die wir in existierenden Programmen gefunden haben und um schöne Noten zu schaffen, die die besten handgestochenen Partituren imitieren.

| [ << Notensatz ] | [Top][Contents][Index] | [ Literatur >> ] |

| [ < Die Geschichte von LilyPond ] | [ Up : Notensatz ] | [ Notenschriftarten > ] |

1.2 Details des Notensetzens

Die Kunst des Notensatzes wird auch als Notenstich bezeichnet. Dieser Begriff stammt aus dem traditionellen Notendruck1. Noch bis vor etwa 20 Jahren wurden Noten erstellt, indem man sie in eine Zink- oder Zinnplatte schnitt oder mit Stempeln schlug. Diese Platte wurde dann mit Druckerschwärze versehen, so dass sie in den geschnittenen und gestempelten Vertiefungen blieb. Diese Vertiefungen schwärzten dann ein auf die Platte gelegtes Papier. Das Gravieren wurde vollständig von Hand erledigt. Es war darum sehr mühsam, Korrekturen anzubringen, weshalb man von vornherein richtig schneiden musste. Die Kunst des Notenstechens war eine sehr spezialisierte Handwerkskunst, für die ein Handwerker etwa fünf Ausbildungsjahre benötigte, bevor der den Meistertitel tragen durfte. Weitere fünf Jahre waren erforderlich, um diese Kunst wirklich zu beherrschen.

LilyPond wurde von den handgestochenen traditionellen Noten inspiriert, die in der ersten Hälfte des 20. Jahrhunderts von europäischen Notenverlagen herausgegeben wurden (insbesondere Bärenreiter, Duhem, Durand, Hofmeister, Peters und Scott). Sie werden teilweise als der Höhepunkt des traditionellen Notenstichs angesehen. Beim Studium dieser Editionen haben wir eine Menge darüber gelernt, was einen gut gesetzten Musikdruck ausmacht und welche Aspekte des handgestochenen Notensatzes wir in LilyPond imitieren wollten.

| Notenschriftarten | ||

| Optischer Ausgleich | ||

| Hilfslinien | ||

| Optische Größen | ||

| Warum der große Aufwand? |

| [ << Notensatz ] | [Top][Contents][Index] | [ Literatur >> ] |

| [ < Details des Notensetzens ] | [ Up : Details des Notensetzens ] | [ Optischer Ausgleich > ] |

Notenschriftarten

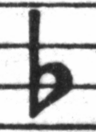

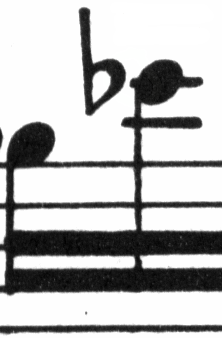

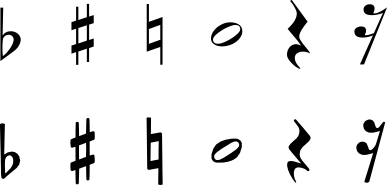

Die Abbildung unten illustriert den Unterschied zwischen traditionellem Notensatz und einem typischen Computersatz. Das linke Bild zeigt ein eingescanntes b-Vorzeichen einer handgestochenen Bärenreiter-Edition, das rechte Bild hingegen ein Symbol aus einer 2000 herausgegebenen Edition der selben Noten. Obwohl beide Bilder mit der gleichen Tintenfarbe gedruckt sind, wird die frühere Version dunkler: die Notenlinien sind dicker und das Bärenreiter-b hat ein rundliches, beinahe sinnliches Aussehen. Der rechte Scan hingegen hat dünnere Linien und eine gerade Form mit scharfen Ecken und Kanten.

|  | |

| Bärenreiter (1950) | Henle (2000) |

Als wir uns entschlossen hatten, ein Programm zu schreiben, das die Typographie des Notensatzes beherrscht, gab es keine freien Musikschriftarten, die unserem geplanten eleganten Notenbild passen würden. Unbeirrt schufen wir eine Schriftart und dazu einen Computerfont mit den musikalischen Symbolen, wobei wir uns an den schönen Musikdrucken der handgestochenen Noten orientierten. Ohne diese Erfahrung hätten wir nie verstanden, wie hässlich die Schriftarten waren, die wir zuerst bewunderten.

Unten ein Beispiel zweier Notenschriftarten. Das obere Beispiel ist der Standard im Sibelius-Programm (die Opus-Schriftart), das untere unsere eigene LilyPond-Schriftart.

Die LilyPond-Symbole sind schwerer und ihre Dicke ist durchgängiger, wodurch sie einfacher zu lesen sind. Feine Enden, wie etwa die Seiten der Viertelpause, sollten nicht als scharfe Spitzen enden, sondern etwas abgerundet. Das liegt daran, dass scharfe Enden der Stempel sehr fragil sind und sich schnell durch die Verwendung abnutzen. Zusammengefasst muss die Schwärze der Schriftart sehr vorsichtig mit der Schwärze von Notenlinien, Balken und Bögen abgeglichen werden, um ein starkes, aber doch ausgewogenes Gesamtbild zu ergeben.

Einige weitere Besonderheiten: der Notenkopf der Halben ist nicht elliptisch, sondern etwas rautenförmig. Der vertikale Hals des b-Symbols ist schwach keilförmig nach oben hin. Das Kreuz und das Auflösungszeichen sind einfacher aus der Entfernung zu unterscheiden, weil ihre schrägen Linien eine andere Neigung haben und die vertikalen Linien dicker sind.

| [ << Notensatz ] | [Top][Contents][Index] | [ Literatur >> ] |

| [ < Notenschriftarten ] | [ Up : Details des Notensetzens ] | [ Hilfslinien > ] |

Optischer Ausgleich

Die Aufteilung der Noten in der Horizontalen sollte die Dauer der jeweiligen Note widerspiegeln. Wie wir jedoch im Beispiel der Bach-Suite oben sehen konnten, orientieren sich viele moderne Partituren an den Dauern mit mathematischer Präzision, was zu schlechten Ergebnissen führt. Im nächsten Beispiel ist ein Motiv zweimal dargestellt: das erste Mal mit exakter mathematischer Aufteilung, das zweite Mal mit Korrekturen. Welches Beispiel spricht Sie mehr an?

In jedem Takt in diesem Ausschnitt kommen Noten vor, die in einem gleichmäßigen Rhythmus gespielt werden. Die Abstände sollten das widerspiegeln. Leider lässt uns aber das Auge im Stich: es beachtet nicht nur den Abstand von aufeinander folgenden Notenköpfen, sondern auch den ihrer Hälse. Also müssen Noten, deren Hälse in direkter Folge zuerst nach oben und dann nach unten ausgerichtet sind, weiter auseinander gezogen werden, während die unten/oben-Folge engere Abstände fordert, und das alles auch noch in Abhängigkeit von der vertikalen Position der Noten. Das untere Beispiel ist mit dieser Korrektur gesetzt. Im oberen Beispiel hingegen bilden sich für das Auge bei unten/oben-Folgen Notenklumpen. Ein Notenstechermeister hätte die Notenaufteilung angepasst, sodass die angenehm zu lesen ist.

Die Algorithmen zur Platzaufteilung von LilyPond berechnen sogar die Taktstriche mit ein, weshalb die letzte Noten mit Hals nach oben im richtig platzierten Beispiel etwas mehr Platz vor dem Taktstrich erhält, damit sie nicht gedrängt wirkt. Ein Hals nach unten würde diesen Ausgleich nicht benötigen.

| [ << Notensatz ] | [Top][Contents][Index] | [ Literatur >> ] |

| [ < Optischer Ausgleich ] | [ Up : Details des Notensetzens ] | [ Optische Größen > ] |

Hilfslinien

Hilfslinien stellen eine typographische Herausforderung dar: sie machen es schwerer, die Notensymbole dicht anzuordnen und sie müssen klar genug sein, dass sich die Tonhöhe mit einem schnellen Blick erkennen lässt. Im Beispiel unten können wir sehen, dass Hilfslinien dicker als normale Notenlinien sein sollten und dass ein gelernter Notenstecher eine Hilfslinie verkürzt, um dichteres Platzieren von Versetzungszeichen zu erlauben. Wir haben diese Eigenschaft in den Notensatz von LilyPond eingebaut.

|  |

| [ << Notensatz ] | [Top][Contents][Index] | [ Literatur >> ] |

| [ < Hilfslinien ] | [ Up : Details des Notensetzens ] | [ Warum der große Aufwand? > ] |

Optische Größen

Noten werden in verschiedenen Größen gedruckt. Ursprünglich hatte man hierzu Stempel in verschiedenen Größen, was gleichzeitig heißt, dass jeder Stempel so beschaffen war, dass er für seine Größe ein ideales Abbild erzeugte. Mit den digitalen Fonts kann ein einziger Umriss mathematisch skaliert werden, um eine beliebige Größe zu erzeugen, was sehr viele Vorteile hat. In kleinen Größen erscheinen die Symbole jedoch zu dünn.

Für LilyPond haben wir Schriftarten mit einer Reihe von Dicken erstellt, die jeweils einer Notengröße entsprechen. Hier ein LilyPond-Notensatz mit der Systemgröße 26:

und hier die gleichen Noten mit Systemgröße 11, anschließend um 236% vergrößert, damit das Bild in exakt der gleichen Größe wie das vorige erscheint:

Bei kleineren Größen benutzt LilyPond proportional dickere Notenlinien, sodass das Notenbild immer noch gut zu lesen ist.

| [ << Notensatz ] | [Top][Contents][Index] | [ Literatur >> ] |

| [ < Optische Größen ] | [ Up : Details des Notensetzens ] | [ Automatisierter Notensatz > ] |

Warum der große Aufwand?

Musiker sind üblicherweise zu sehr damit beschäftigt, die Musik aufzuführen, als dass sie das Aussehen der Noten studieren könnten; darum mag diese Beschäftigung mit typographischen Details akademisch wirken. Das ist sie aber nicht. Notenmaterial ist Aufführungsmaterial: alles muss unternommen werden, damit der Musiker die Aufführung besser bewältigt, und alles, das unklar oder unangenehm ist, ist eine Hindernis.

Der dichtere Eindruck, den die dickeren Notenlinien und schwereren Notationssymbole schaffen, eignet sich besser für Noten, die weit vom Leser entfernt stehen, etwa auf einem Notenständer. Eine sorgfältige Verteilung der Zwischenräume erlaubt es, die Noten sehr dicht zu setzen, ohne dass die Symbole zusammenklumpen. Dadurch werden unnötige Seitenumbrüche vermieden, so dass man nicht so oft blättern muss.

Dies sind die Anforderungen der Typographie: Das Layout sollte schön sein – nicht nur aus Selbstzweck, sondern vor allem um dem Leser zu helfen. Für Aufführungsmaterial ist das umso wichtiger, denn Musiker haben eine begrenzte Aufnahmefähigkeit. Je weniger Mühe nötig ist, die Noten zu erfassen, desto mehr Zeit bleibt für die Gestaltung der eigentlichen Musik. Das heißt: Gute Typographie führt zu besseren Aufführungen!

Die Beispiele haben gezeigt, dass der Notensatz eine subtile und komplexe Kunst ist und gute Ergebnisse nur mit viel Erfahrung erlangt werden können, die Musiker normalerweise nicht haben. LilyPond stellt unser Bemühen dar, die graphische Qualität handgestochener Notenseiten ins Computer-Zeitalter zu transportieren und sie für normale Musiker erreichbar zu machen. Wir haben unsere Algorithmen, die Gestalt der Symbole und die Programm-Einstellungen darauf abgestimmt, einen Ausdruck zu erzielen, der der Qualität der alten Editionen entspricht, die wir so gerne betrachten und aus denen wir gerne spielen.

| [ << Notensatz ] | [Top][Contents][Index] | [ Literatur >> ] |

| [ < Warum der große Aufwand? ] | [ Up : Notensatz ] | [ Schönheitswettbewerb > ] |

1.3 Automatisierter Notensatz

Dieser Abschnitt beschreibt, was benötigt wird um ein Programm zu schreiben, welches das Layout von gestochenen Noten nachahmen kann: eine Methode, dem Computer gute Layouts zu erklären und detailliertes Vergleichen mit echten Notendrucken.

| Schönheitswettbewerb | ||

| Verbessern durch Benchmarking | ||

| Alles richtig machen |

| [ << Notensatz ] | [Top][Contents][Index] | [ Literatur >> ] |

| [ < Automatisierter Notensatz ] | [ Up : Automatisierter Notensatz ] | [ Verbessern durch Benchmarking > ] |

Schönheitswettbewerb

Wie sollen wir also jetzt die Typographie anwenden? Anders gesagt: welcher von den drei Konfigurationen sollte für den folgenden Bogen ausgewählt werden?

Es gibt wenige Bücher über die Kunst des Notensatzes. Leider haben sie nur Daumenregeln und einige Beispiele zu bieten. Solche Regeln können sehr informativ sein, aber sie sind weit entfernt von einem Algorithmus, den wir in unser Programm einbauen könnten. Indem man die Anweisungen der Literatur anwendet, kommt man zu Algorithmen mit sehr vielen manuellen Ausnahmen. Alle die möglichen Fälle zu analysieren stellt sehr viel Arbeit dar und meistens werden dennoch nicht alle Fälle vollständig abgedeckt:

(Bildquelle: Ted Ross, The Art of Music Engraving)

Anstatt zu versuchen, für jedes mögliche Szenario eine passende Layoutregel zu definieren, müssen wir nur die Regeln genau genug beschreiben, sodass LilyPond die Gefälligkeit von mehreren Alternativen selber einschätzen kann. Dann errechnen wir für jede mögliche Konfiguration eine Hässlichkeits-Rangliste und wir wählen die Konfiguration aus, die am wenigsten hässlich ist.

Zum Beispiel hier drei mögliche Konfiguration eines Legatobogens, und LilyPond hat jeder Konfiguration „Hässlichkeitspunkte“ verliehen. Das erste Beispiel erhält 15.39 Punkte, weil einer der Notenköpfe angeschnitten wird:

Das zweite Beispiel ist schöner, aber der Bogen beginnt weder noch endet er an den Notenköpfen. Hier werden 1.71 Punkte auf der linken und 9.37 Punkte auf der rechten Seite verliehen, plus weiteren 2 Punkten, weil der Bogen aufsteigt, während die Melodie absteigt. Insgesamt also 13.08 Punkte:

Der letzte Bogen erhält 10.04 Punkte für die Lücke rechts und 2 Punkte für die Neigung nach oben, aber er ist die schönste der drei Varianten, sodass LilyPond ihn auswählt:

Diese Technik ist sehr allgemein und wird benutzt, um optimale Entscheidungen für Bögenkonfigurationen, Bindebögen und Punkten in Akkorden, Zeilenumbrüche und Seitenumbrüche zu erhalten. Die Ergebnisse dieser Entscheidungen können durch einen Vergleich mit handgestochenen Noten eingeschätzt werden.

| [ << Notensatz ] | [Top][Contents][Index] | [ Literatur >> ] |

| [ < Schönheitswettbewerb ] | [ Up : Automatisierter Notensatz ] | [ Alles richtig machen > ] |

Verbessern durch Benchmarking

Die Ausgabe von LilyPond hat sich schrittweise mit der Zeit verbessert, und sie verbessert sich weiter, indem sie immer wieder mit handgestochenen Noten verglichen wird.

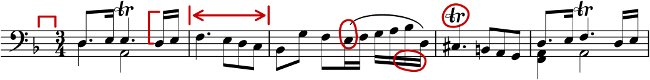

Hier als Beispiel eine Zeile eines Benchmark-Stückes aus einer handgestochenen Notenedition (Bärenreiter BA320):

und die gleiche Zeile als Satz einer sehr alten LilyPond-Version (Version 1.4, Mai 2001):

Die Ausgabe von LilyPond 1.4 ist auf jeden Fall leserlich, aber ein ausführlicher Vergleich mit der Vorlage zeigt viele Fehler in den Formatierungsdetails:

- vor der Taktangabe ist nicht genug Platz

- die Hälse der bebalkten Noten sind zu lang

- der zweite und vierte Takt sind zu schmal

- der Bogen sieht ungeschickt aus

- das Triller-Symbol ist zu groß

- die Hälse sind zu dünn

(Es gibt auch zwei fehlende Notenköpfe, verschiedene editorische Anweisungen, die Fehler und eine falsche Tonhöhe!)

Indem die Layoutregeln und das Design der Schriftarten angepasst wurde, hat sich die Ausgabe sehr stark verbessert. Vergleichen Sie das gleiche Referenzbeispiel und die Ausgabe der aktuellen LilyPond-Version (2.25.16):

Die jetzige Ausgabe ist kein Klon der Referenzedition, aber sie ist sehr viel näher an einer Publikationsqualität.

| [ << Notensatz ] | [Top][Contents][Index] | [ Literatur >> ] |

| [ < Verbessern durch Benchmarking ] | [ Up : Automatisierter Notensatz ] | [ Ein Programm bauen > ] |

Alles richtig machen

Wir können auch die Fähigkeiten von LilyPond, Notensatzentscheidungen alleine zu fällen, messen, indem wir die Ausgabe von LilyPond mit der Ausgabe eines kommerziellen Notensatzprogramms vergleichen. In diesem Fall haben wir Finale 2008 genommen, eines der beliebtesten Notensatzprogramme, insbesondere in Nordamerika. Sibelius ist Finales hauptsächlicher Gegenspieler, offensichtlich vor allem in Europa verbreitet.

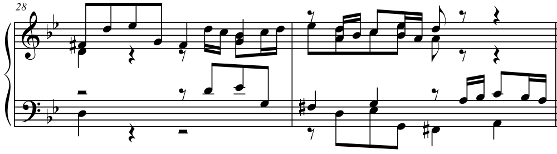

Für unseren Vergleich haben wir uns für die Fuge in G-Moll aus dem Wohltemperierten Clavier 1, BWV 861 von J. S. Bach entschieden, mit dem Hauptthema:

In unserem Vergleich setzten wir die letzten sieben Takte des Stückes (28–34) in Finale und LilyPond. Das ist der Punkt, an der das Thema als dreistimmige Engführung in den Schlussabschnitt überleitet. In der Finale-Version haben wir der Versuchung widerstanden, jedwede Anpassungen abweichend vom Standard vorzunehmen, weil wir zeigen wollen, welche Dinge von den beiden Programmen ohne Hilfeleistung richtig gemacht werden. Die einzigen größeren Änderungen, die wir vorgenommen haben, war die Anpassung der Seitengröße an die Seitengröße dieses Aufsatzes und die Begrenzung der Noten auf zwei Systeme, um den Vergleich einfacher zu machen. In der Standardeinstellung Finale hätte zwei Zeilen mit je drei Takten und schließlich eine letzte Zeile gesetzt, die nur einen einzigen Takt enthält.

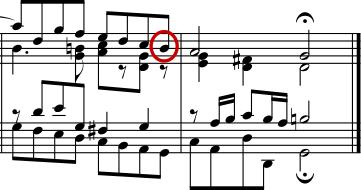

Viele der Unterschiede zwischen den beiden Sätzen finden sich in den Takten 28–29, hier zuerst in Finales Version, dann in der Version von LilyPond:

Einige der Mängel des nicht editierten Finale-Satzes beinhalten:

- Die meisten Balken sind zu weit vom Notensystem entfernt. Ein Balken, der zum Zentrum des Systems zeigt, sollte etwa die Länge einer Oktave haben, aber Notensetzer verkürzen die Länge, wenn der Balken in polyphonen Situationen aus dem System herauszeigt. Die Bebalkung von Finale kann einfach mit ihrem Patterson Beams-Plugin verbessert werden, aber wir haben diesen Schritt für dieses Beispiel ausgelassen.

- Finale passt die Position von ineinander greifenden Notenköpfen nicht an, sodass die Noten sehr schwer lesbar werden, wenn die untere und obere Stimme zeitweise ausgetauscht werden:

- Finale positioniert alle Pausen an einer festen Position auf dem System. Der Benutzer kann sie anpassen, wie er es richtig findet, aber das Programm unternimmt keinen Versuch, den Inhalt der anderen Stimme mit einzubeziehen. Durch einen Glücksfall kommen keine wirklichen Kollisionen zwischen Noten und Pausen in diesem Beispiel vor, aber das liegt mehr an der Position der Noten als an der der Pausen. Anders gesagt: Bach verdient mehr Aufmerksamkeit um vollständige Kollisionen zu vermeiden als Finale ihm gönnt.

Dieses Beispiel soll nicht suggerieren, dass man mit Finale nicht Notensatz in Publikationsqualität erstellen könnte. Das Programm ist durchaus dazu fähig, wenn ein erfahrener Benutzer genug Zeit und Fähigkeit mitbringt. Einer der fundamentalen Unterschiede zwischen LilyPond und kommerziellen Notensatzprogrammen ist, dass LilyPond versucht, den Aufwand an menschlicher Intervention auf ein absolutes Minimum zu reduzieren, während andere Programme versuchen, ein attraktives Programmfenster zu bieten, in dem die Anpassungen vorgenommen werden können.

Einen besonders hervorstechenden Mangel von Finale ist ein fehlendes b-Vorzeichen in Takt 33:

Das b-Symbol wird benötigt, um das Auflösungzeichen im selben Takt rückgängig zu machen, aber Finale lässt es aus, weil es in einer anderen Stimme vorkommt. Der Benutzer muss nicht nur daran denken, ein Balken-Plugin zu starten und die Notenköpfe und Pausen neu anzuordnen, er muss auch jeden Takt prüfen, ob Versetzungszeichen aus anderen Stimmen korrigiert werden müssen, damit nicht ein Notensatzfehler die Probe unnötig unterbricht.

Wenn Sie diese Beispiel noch detaillierter betrachten wollen, können Sie den vollen siebentaktigen Ausschnitt am Ende dieses Aufsatzes als Notensatz in vier unterschiedlichen publizierten Editionen finden. Nähere Betrachtung zeigt, dass es einige akzeptable Variationen zwischen den handgestochenen Beispielen gibt, dass LilyPond aber ziemlich guten Notensatz im Rahmen dieser Variationen produziert. Auch die LilyPond-Ausgabe hat noch ihre Fehler: sie ist beispielsweise etwas zu aggressiv bei der Verkürzung einiger Hälse – hier ist also noch Raum für weitere Entwicklung und Feineinstellung.

Natürlich hängt Typographie vom menschlichen Urteil der Erscheinung ab, sodass Menschen nicht vollständig ersetzt werden können. Viel der eintönigen Arbeit kann jedoch automatisiert werden. Wenn LilyPond die meisten üblichen Situationen richtig löst, ist das schon eine große Verbesserung gegenüber existierender Software. Im Laufe der Jahre wir das Programm immer besser und macht mehr und mehr Sachen automatisch, sodass manuelles Eingreifen immer seltener wird. Wo manuelle Anpassungen benötigt werden, wurde die Struktur von LilyPond mit Flexibilität im Hinterkopf geplant.

| [ << Notensatz ] | [Top][Contents][Index] | [ Literatur >> ] |

| [ < Alles richtig machen ] | [ Up : Notensatz ] | [ Die Darstellung der Musik > ] |

1.4 Ein Programm bauen

Dieser Abschnitt beschreibt einige der Entscheidungen, die wir während des Programmierens für das Design von LilyPond getroffen haben.

| Die Darstellung der Musik | ||

| Welche Symbole? | ||

| Flexible Architektur |

| [ << Notensatz ] | [Top][Contents][Index] | [ Literatur >> ] |

| [ < Ein Programm bauen ] | [ Up : Ein Programm bauen ] | [ Welche Symbole? > ] |

Die Darstellung der Musik

Idealerweise ist das Eingabeformat für ein komplexes Satzsystem die abstrakte Beschreibung des Inhaltes. In diesem Fall wäre das die Musik selber. Das stellt uns aber vor ein ziemlich großes Problem, denn wie können wir definieren, was Musik wirklich ist? Anstatt darauf eine Antwort zu suchen, haben wir die Frage einfach umgedreht. Wir schreiben ein Programm, das den Notensatz beherrscht und machen das Format so einfach wie möglich. Wenn es nicht mehr vereinfacht werden kann, haben wir per Definition nur noch den reinen Inhalt. Unser Format dient als die formale Definition eines Musiktextes.

Die Syntax ist gleichzeitig die Benutzerschnittstelle bei LilyPond, darum soll sie einfach zu schreiben sein; z. B. bedeutet

{

c'4 d'8

}

dass eine Viertel c’ und eine Achtel d’ erstellt werden sollen, wie in diesem Beispiel:

In kleinem Rahmen ist diese Syntax sehr einfach zu benutzen. In größeren Zusammenhängen aber brauchen wir Struktur. Wie sonst kann man große Opern oder Symphonien notieren? Diese Struktur wird gewährleistet durch sog. music expressions (Musikausdrücke): indem kleine Teile zu größeren kombiniert werden, kann komplexere Musik dargestellt werden. So etwa hier:

f'4

Gleichzeitig erklingende Noten werden hinzugefügt, indem man alle in << und >> einschließt.

<<c4 d4 e4>>

Um aufeinanderfolgende Noten darzustellen, werden sie in geschweifte Klammern gefasst:

{ … }

{ f4 <<c4 d4 e4>> }

Dieses Gebilde ist in sich wieder ein Ausdruck, und kann

daher mit einem anderen Ausdruck kombiniert werden (hier mit einer Halben), wobei <<, \\, and >> eingesetzt wird:

<< g2 \\ { f4 <<c4 d4 e4>> } >>

Solche geschachtelten Strukturen können sehr gut in einer kontextunabhängigen Grammatik beschrieben werden. Der Programmcode für den Satz ist auch mit solch einer Grammatik erstellt. Die Syntax von LilyPond ist also klar und ohne Zweideutigkeiten definiert.

Die Benutzerschnittstelle und die Syntax werden als erstes vom Benutzer wahrgenommen. Teilweise sind sie eine Frage des Geschmackes und werden viel diskutiert. Auch wenn Geschmacksfragen ihre Berechtigung haben, sind sie nicht sehr produktiv. Im großen Rahmen von LilyPond spielt die Eingabe-Syntax nur eine geringe Rolle, denn eine logische Syntax zu schreiben ist einfach, guten Formatierungscode aber sehr viel schwieriger. Das kann auch die Zeilenzahl der Programmzeilen zeigen: Analysieren und Darstellen nimmt nur etwa 10% des Codes ein:

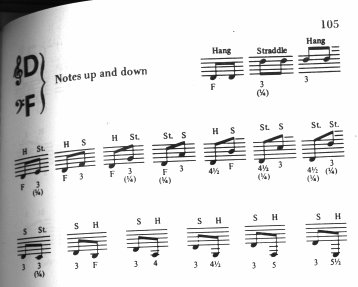

Während wir die Strukturen von LilyPond entwickelten, machten wir einige Entscheidungen, die sich von anderen Programmen unterscheiden. Nehmen wir etwa die hierarchische Natur der Musiknotation:

In diesem Fall werden Tonhöhen in Akkorde gruppiert, die zu Takten gehören, welche wiederum zu Notensystemen gehören. Das erinnert an die saubere Struktur von geschachtelten Kästen:

Leider ist die Struktur nur sauber, weil sie auf einige sehr beschränkte Annahmen basiert. Das wird offensichtlich, wenn man ein komplizierteres Beispiel heranzieht:

In diesem Beispiel beginnen Systeme plötzlich und enden plötzlich, Stimmen springen zwischen den Systemen herum und die Systeme haben unterschiedliche Taktarten. Viele Software-Pakte würden sehr damit zu kämpfen haben, dieses Beispiel darzustellen, weil sie nach dem Prinzip von geschachtelten Kästen aufgebaut sind. In LilyPond dagegen haben wir versucht, die Struktur und das Eingabeformat so flexibel wie möglich zu gestalten.

| [ << Notensatz ] | [Top][Contents][Index] | [ Literatur >> ] |

| [ < Die Darstellung der Musik ] | [ Up : Ein Programm bauen ] | [ Flexible Architektur > ] |

Welche Symbole?

Während des Notensatzprozesses entscheidet sich, wo Symbole platziert werden. Das kann aber nur gelingen, wenn vorher entschieden wird, welche Symbole gesetzt werden sollen, also welche Art von Notation benutzt werden soll.

Die heutige Notation ist ein System zur Musikaufzeichnung, das sich über die letzten 1000 Jahre entwickelt hat. Die Form, die heute üblicherweise benutzt wird, stammt aus der frühen Renaissance. Auch wenn sich die grundlegenden Formen (also die Notenköpfe, das Fünfliniensystem) nicht verändert haben, entwickeln sich die Details trotzdem immer noch weiter, um die Errungenschaften der Neuen Musik darstellen zu können. Die Notation umfasst also 500 Jahre Musikgeschichte. Ihre Anwendung reicht von monophonen Melodien bis zu ungeheuer komplexem Kontrapunkt für großes Orchester.

Wie bekommen wir dieses vielköpfige Monster zu fassen und in die

Fesseln eines Computerprogrammes zu legen?

Unsere Lösung ist es, das Problem in kleine (programmierbare) Happen zu zerteilen, so dass jede Art

von Symbol durch ein eigenes Modul, als Plugin bezeichnet,

verarbeitet werden kann. Jedes Plugin ist vollständig modular

und unabhängig und kann unabhängig entwickelt und verbessert

werden. Derartige Plugins werden engraver genannt,

analog zu den Notenstechern (engl. engraver), die musikalische

Ideen in graphische Symbole übersetzen.

Im nächsten Beispiel wird gezeigt, wie mit dem Plugin für die Notenköpfe,

dem Note_heads_engraver („Notenkopfstecher“) der Satz begonnen wird.

Dann fügt ein Staff_symbol_engraver („Notensystemstecher“)

die Notenlinien hinzu.

Der Clef_engraver („Notenschlüsselstecher“) definiert

eine Referenzstelle für das System.

Der Stem_engraver („Halsstecher“) schließlich fügt

Hälse hinzu.

Dem Stem_engraver wird jeder Notenkopf mitgeteilt,

der vorkommt. Jedes Mal, wenn ein Notenkopf erscheint (oder mehrere bei

einem Akkord), wird ein Hals-Objekt erstellt und an den

Kopf geheftet. Wenn wir dann noch Engraver für Balken, Bögen,

Akzente, Versetzungszeichen, Taktstriche, Taktangaben und Tonartbezeichnungen

hinzufügen, erhalten wir eine vollständige Notation.

Dieses System funktioniert gut für monophone Musik, aber wie geht es mit Polyphonie? Hier müssen sich mehrere Stimmen ein System teilen.

In diesem Fall benutzen beide Stimmen das System und die Vorzeichen gemeinsam, aber die Hälse, Bögen, Balken usw. sind jeder einzelnen Stimme eigen. Die Engraver müssen also gruppiert werden. Die Köpfe, Hälse, Bögen usw. werden in einer Gruppe mit dem Namen „Voice context“ (Stimmenkontext) zusammengefasst, die Engraver für den Schlüssel, die Vorzeichen, Taktstriche usw. dagegen in einer Gruppe mit dem Namen „Staff context“ (Systemkontext). Im Falle von Polyphonie hat ein Staff-Kontext dann also mehr als nur einen Voice-Kontext. Auf gleiche Weise können auch mehrere Staff-Kontexte in einen großen Score-Kontext (Partiturkontext) eingebunden werden. Der Score-Kontext ist auf der höchsten Ebene der Kontexte.

Siehe auch

Referenz der Interna: Contexts.

| [ << Notensatz ] | [Top][Contents][Index] | [ Literatur >> ] |

| [ < Welche Symbole? ] | [ Up : Ein Programm bauen ] | [ LilyPond die Arbeit überlassen > ] |

Flexible Architektur

Als wir anfingen, haben wir LilyPond vollständig in der Programmiersprache C++ geschrieben. Das hieß, dass der Funktionsumfang des Programms vollständig durch die Programmierer festgelegt war. Das stellte sich aus einer Reihe von Gründen als unzureichend heraus:

- Wenn LilyPond Fehler macht, muss der Benutzer die Einstellungen ändern können. Er muss also Zugang zur Formatierungsmaschinerie haben. Deshalb können die Regeln und Einstellungen nicht beim Kompilieren des Programms festgelegt werden, sondern sie müssen zugänglich sein, während das Programm aktiv ist.

- Notensatz ist eine Frage des Augenmaßes, und damit auch vom Geschmack abhängig. Benutzer können mit unseren Entscheidungen unzufrieden sein. Darum müssen also auch die Definitionen des typographischen Stils dem Benutzer zugänglich sein.

- Schließlich verfeinern wir unseren Formatierungsalgorithmus immer weiter, also müssen die Regeln auch flexibel sein. Die Sprache C++ zwingt zu einer bestimmten Gruppierungsmethode, die nicht den Regeln für den Notensatz entspricht.

Diese Probleme wurden angegangen, indem ein Übersetzer für die Programmiersprache Scheme integriert wurde und Teile von LilyPond in Scheme neu geschrieben wurden. Die derzeitige Formatierungsarchitektur ist um die Notation von graphischen Objekten herum aufgebaut, die von Scheme-Variablen und -Funktionen beschrieben werden. Diese Architektur umfasst Formatierungsregeln, typographische Stile und individuelle Formatierungsentscheidungen. Der Benutzer hat direkten Zugang zu den meisten dieser Einstellungen.

Scheme-Variablen steuern Layout-Entscheidungen. Zum Beispiel haben viele graphische Objekte eine Richtungsvariable, die zwischen oben und unten (oder rechts und links) wählen kann. Hier etwa sind zwei Akkorde mit Akzenten und Arpeggien. Beim ersten Akkord sind alle Objekte nach unten (oder links) ausgerichtet, beim zweiten nach oben (rechts).

Der Prozess des Notensetzens besteht für das Programm darin, die Variablen der graphischen Objekte zu lesen und zu schreiben. Einige Variablen haben festgelegte Werte. So ist etwa die Dicke von vielen Linien – ein Charakteristikum des typographischen Stils – von vornherein festgelegt. Wenn sie geändert werden, ergibt sich ein anderer typographischer Eindruck.

Formatierungsregeln sind auch vorbelegte Variablen. Zu jedem Objekt gehören Variablen, die Prozeduren enthalten. Diese Prozeduren machen die eigentliche Satzarbeit aus, und wenn man sie durch andere ersetzt, kann die Darstellung von Objekten verändert werden. Im nächsten Beispiel wird die Regel, nach der die Notenköpfe gezeichnet werden, während des Ausschnitts verändert.

| [ << Notensatz ] | [Top][Contents][Index] | [ Literatur >> ] |

| [ < Flexible Architektur ] | [ Up : Notensatz ] | [ Notensatzbeispiele (BWV 861) > ] |

1.5 LilyPond die Arbeit überlassen

Wir haben LilyPond als einen Versuch geschrieben, wie man die Kunst des Musiksatzes in ein Computerprogramm gießen kann. Dieses Programm kann nun dank vieler harter Arbeitsstunden benutzt werden, um sinnvolle Aufgaben zu erledigen. Die einfachste ist dabei der Notendruck.

Indem wir Akkordsymbole und einen Text hinzufügen, erhalten wir ein Liedblatt.

Mehrstimmige Notation und Klaviermusik kann auch gesetzt werden. Das nächste Beispiel zeigt einige etwas exotischere Konstruktionen:

Die obenstehenden Beispiele wurde manuell erstellt, aber das ist nicht die einzige Möglichkeit. Da der Satz fast vollständig automatisch abläuft, kann er auch von anderen Programmen angesteuert werden, die Musik oder Noten verarbeiten. So können etwa ganze Datenbanken musikalischer Fragmente automatisch in Notenbilder umgewandelt werden, die dann auf Internetseiten oder in Multimediapräsentation Anwendung finden.

Dieser Aufsatz zeigt eine weitere Möglichkeit: Die Noten werden als

reiner Text eingegeben und können darum sehr einfach integriert werden

in andere textbasierte Formate wie etwa LaTeX, HTML oder, wie in diesem

Fall, Texinfo. Mithilfe des Programmes lilypond-book,

das in LilyPond inbegriffen ist, werden die Fragmente mit

Notenbildern ersetzt und in die produzierte PDF- oder HTML-Datei

eingefügt. Ein weiteres Beispiel ist die von LilyPond unabhängige

Erweiterung OOoLilyPond für OpenOffice.org, mit der es sehr einfach

ist, Musikbeispiele in Dokumente einzufügen.

Zu mehr Beispielen, wie LilyPond sich in Aktion verhält, für vollständige Dokumentation und das Programm LilyPond besuchen Sie unsere Webseite: www.lilypond.org.

| [ << Notensatz ] | [Top][Contents][Index] | [ Literatur >> ] |

| [ < LilyPond die Arbeit überlassen ] | [ Up : Notensatz ] | [ Literatur > ] |

1.6 Notensatzbeispiele (BWV 861)

Dieser Abschnitt enthält vier Referenz-Notenstiche und zwei computergesetzte Versionen der Fuge G-Moll aus dem Wohltemperierten Clavier I (BWV 681) von J. S. Bach (die letzten sieben Takte).

Bärenreiter BA5070 (Neue Ausgabe Sämtlicher Werke, Serie V, Band 6.1, 1989):

Bärenreiter BA5070 (Neue Ausgabe Sämtlicher Werke, Serie V, Band 6.1, 1989), eine alternative musikalische Quelle. Neben den musikalischen Unterschieden sind hier auch ein paar unterschiedliche Notensatzentscheidungen getroffen worden, sogar vom selben Herausgeber in der selben Edition:

Breitkopf & Härtel, bearbeitet von Ferruccio Busoni (Wiesbaden, 1894), auch in der Petrucci Music Library (IMSLP #22081) erhältlich. Die editorischen Bezeichnungen (Fingersatz, Artikulation usw.) wurde entfernt, um bessere Vergleichbarkeit mit den anderen Editionen zu bieten:

Bach-Gesellschaft Edition (Leipzig, 1866), erhältlich in der Petrucci Music Library (IMSPL #02221):

Finale 2008:

LilyPond, version 2.25.16:

| [ << Notensatz ] | [Top][Contents][Index] | [ GNU Free Documentation License >> ] |

| [ < Notensatzbeispiele (BWV 861) ] | [ Up : Top ] | [ Kurze Literaturliste > ] |

2 Literatur

Hier eine Liste der Literatur, die in LilyPond benutzt wurde:

| 2.1 Kurze Literaturliste | ||

| 2.2 Lange Literaturliste |

| [ << Literatur ] | [Top][Contents][Index] | [ GNU Free Documentation License >> ] |

| [ < Literatur ] | [ Up : Literatur ] | [ Lange Literaturliste > ] |

2.1 Kurze Literaturliste

Wenn Sie mehr über Notation und den Notenstich erfahren wollen, sind hier einige interessante Titel gesammelt.

- Ignatzek 1995

Klaus Ignatzek, Die Jazzmethode für Klavier. Schott’s Söhne 1995. Mainz, Germany ISBN 3-7957-5140-3.

Eine praktische Einführung zum Spielen von Jazz auf dem Klavier. Eins der ersten Kapitel enthält einen Überblick über die Akkorde, die im Jazz verwendet werden.

- Gerou 1996

-

Tom Gerou and Linda Lusk, Essential Dictionary of Music Notation. Alfred Publishing, Van Nuys CA ISBN 0-88284-768-6.

Eine ausführliche, alphabetische Liste vieler Belange des Musiksatzes und der Notation; die üblichen Fälle werden behandelt.

- Read 1968

Gardner Read, Music Notation: A Manual of Modern Practice. Taplinger Publishing, New York (2nd edition).

Ein Klassiker für die Musiknotation.

- Ross 1987

Ted Ross, Teach yourself the art of music engraving and processing. Hansen House, Miami, Florida 1987.

Dieses Buch handelt vom Musiksatz, also vom professionellen Notenstich. Hier sind Anweisungen über Stempel, die Benutzung von Stiften und nationale Konventionen versammelt. Die Kapitel zu Reproduktionstechniken und der historische Überblick sind auch interessant.

- Schirmer 2001

The G.Schirmer/AMP Manual of Style and Usage. G.Schirmer/AMP, NY, 2001.

Dieses Handbuch setzt den Fokus auf die Herstellung von Drucksachen für den Schirmer-Verlag. Hier werden viele Details behandelt, die sich in anderen Notationshandbüchern nicht finden. Es gibt auch einen guten Überblick, was nötig ist, um Drucke in publikationstauglicher Qualität zu produzieren.

- Stone 1980

-

Kurt Stone, Music Notation in the Twentieth Century. Norton, New York 1980.

Dieses Buch enthält einen Überblick über die Notation von moderner E-Musik, beginnt aber mit einem Überblick über bereits existente Praktiken.

| [ << Literatur ] | [Top][Contents][Index] | [ GNU Free Documentation License >> ] |

| [ < Kurze Literaturliste ] | [ Up : Literatur ] | [ GNU Free Documentation License > ] |

2.2 Lange Literaturliste

Notensatzliteraturliste der University of Colorado

- Willi Apel. The notation of polyphonic music, 900-1600. Cambridge, Mass, 1953. Musical notation.

- Ernest Austin. The Story of Music Printing. Lowe and Brydone Printers, Ltd., London. subject: history of music printing and engraving.

- Anna Maria Busse Berger. Mensuration and proportion signs : origins and evolution. Clarendon Press, Oxford, England, 1993. subject: early notation.

- Roger Bowers. Music & Letters, volume 73. August 1992. Some reflection upon notation and proportion in Monteverdi’s mass and vespers.

- Paul Brainard. Current Musicology. Number 50. July-Dec 1992. Proportional notation in the music of Schutz and his contemporaries in the 17th Century.

- Carl Brandt and Clinton Roemer. Standardized Chord Symbol Notation. Roerick Music Co., Sherman Oaks, CA. subject: musical notation.

- Earle Brown. Musical Quarterly, volume 72. Spring 1986. The notation and performance of new music.

- John Cage. Notations. Something Else Press, New York, 1969. Music, Manuscripts, Facsimiles. Facsimiles of holographs from the Foundation for Contemporary Performance Arts, with text by 269 composers, but rearranged using chance operations.,V).

- J Carter. New Paths in Book Collecting. London, 1934. subject: history of music printing and engraving.

- F. Chrsander. A Sketch of the HIstory of Music printing, from the 15th to the 16th century. 18??. subject: history of music printing and engraving.

- Henry Cowell. Our Inadequate Notation. Modern Music, 4(3), 1927. subject: 20th century notation.

- Henry Cowell. New Musical Resources. Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., New York, 1930. subject: 20th century notation.

- O.F. Deutsch. Music Publishers’ Numbers. London, 1946. subject: history of music printing and engraving.

- Suzanne Eggleston. Notes. New periodicals, 51(2):657(7), Dec 1994. A list of new music periodicals covering the period Jun.-Dec. 1994. Includes aims, formats and a description of the contents of each listed periodical. Includes Music Notation News.

- Hubert Foss. Music Printing. Practical Printing and Binding. Oldhams Press Ltd., Long Acre, London. subject: musical notation.

- Jean Charles Francois. Writing without representation, and unreadable notation.. Perspectives of New Music, 30(1):6(15), Winter 1992. subject: Modern music has outgrown notation. While the computer is used to write down music with accuracy never before achieved, the range of modern sounds has surpassed the relevance of the computer...

- David Fuller. The Journal of Musicology, volume 7. Winter 1989. Notes and inegales unjoined: defending a definition. (written-out inequalities in music notation).

- Virginia Gaburo. Notation. Lingua Press, La Jolla, California, 1977. A Lecture about notation, new ideas about.

- Keith A Hamel. A design for music editing and printing software based on notational syntax. Perspectives of New Music, 27(1):70(14), Winter 1989.

- Archibald Jacob. Musical handwriting : or, How to put music on paper : A handbook for all musicians, professional and amateur. Oxford University Press, London, 1947. subject: Musical notation.

- Harold M Johnson. How to write music manuscript an exercise-method handbook for the music student, copyist, arranger, composer, teacher. Carl Fischer, Inc., New York, 1946. subject: Musical notation –Handbooks, manuals.

- David Evan Jones. Perspectives of New Music. 1990. Speech extrapolated. (includes notation).

- H King. Four Hundred Years of Music Printing. London, 1964. subject: history of music printing and engraving.

- A.H King. The 50th Anniversary of Music Printing. 1973.

- O Kinkeldey. Music And Music Printing in Incunabula. Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America, xxvi:89-118, 1932. subject: history of music printing and engraving.

- D.W. Krummel. Graphic Analysis in Application to Early American Engraved Music. Notes, xvi:213, 9 1958. subject: history of music printing and engraving.

- D.W Krummel. Oblong Format in Early Music Books. The Library, 5th ser., xxvi:312, 1971. subject: history of music printing and engraving.

- Jeffrey Lependorf. ?. Perspectives of New Music, 27(2):232(20), Summer 1989. Contemporary notation for the shakuhachi: a primer for composers. (Tradition and Renewal in the Music of Japan).

- G.A Marco. The Earliest Music Printers of Continental Europe: a Checklist of Facsimiles Illustrating Their Work. Charlottesville, Virginia, 1962. subject: history of music printing and engraving.

- K. Meyer and J O’Meara. The Printing of Music, 1473-1934. The Dolphin, ii:171–207, 1935. subject: history of music printing and engraving.

- Raymond Monelle. Comparative Literature, volume 41. Summer 1989. Music notation and the poetic foot.

- A Novello. Some Account of the Methods of Musick Printing, with Specimens of the Various Sizes of Moveable Types and of Other Matters. London, 1847. subject: history of music printing and engraving.

- C.B Oldman. Collecting Musical First Editions. London, 1934. subject: history of music printing and engraving.

- Carl Parrish. The Notation of Medieval Music. Carl Fischer, Inc., New York, 1946. subject: early notation.

- Carl Parrish. The notation of medieval music. Norton, New York, 1957. Musical notation.

- Harry Patch. Genesis of a Music. University of Wisconsin Press, Madison, 1949. subject: early notation.

- B Pattison. Notes on Early Music Printing. The Library, xix:389-421, 1939. subject: history of music printing and engraving.

- Sandra Pinegar. Current Musicology. Number 53. July 1993. The seeds of notation and music paleography.

- Richard Rastall. The notation of Western music : an introduction. St. Martin’s Press, New York, N.Y., 1982. Musical notation.

- Richard Rastall. Music & Letters, volume 74. November 1993. Equal Temperament Music Notation: The Ailler-Brennink Chromatic Notation. Results and Conclusions of the Music Notation Refor by the Chroma Foundation (book reviews).

- Howard Risatti. New Music Vocabulary. University of Illinois Press, Urbana, Illinois, 1975. A Guide to Notational Signs for Contemporary Music.

- Donald W. Krummel \& Stanley Sadie. Music Printing & Publishing. Macmillan Press, 1990. subject: musical notation.

- Norman E Smith. Current Musicology. Number 45-47. Jan-Dec 1990. The notation of fractio modi.

- W Squire. Notes on Early Music Printing. Bibliographica, iii(99), 1897. subject: history of music printing and engraving.

- Robert Steele. The Earliest English Music Printing. London, 1903. subject: history of music printing and engraving.

- Willy Tappolet. La Notation Musicale. Neuchâtel, Paris, 1947. subject: general notation.

- Leo Treitler. The Journal of Musicology, volume 10. Spring 1992. The unwritten and written transmission, of medieval chant and the start-up of musical notation. Notational practice developed in medieval music to address the written tradition for chant which interacted with the unwritten vocal tradition.

- unknown author. Pictorial History of Music Printing. H. and A. Selmer, Inc., Elhardt, Indiana. subject: history of music printing and engraving.

- M.L West. Music & Letters, volume 75. May 1994. The Babylonian musical notation and the Hurrian melodic texts. A new way of deciphering the ancient Babylonian musical notation.

- C.F. Abdy Williams. The Story of Notation. Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York, 1903. subject: general notation.

- Emmanuel Wintermitz. Musical Autographs from Monteverdi to Hindemith. Princeton University Press, Princeton, 1955. subject: history of music printing and engraving.

Computernotation-Bibliographie

- G. Assayaag and D. Timis. A Toolbox for music notation. In Proceedings of the 1986 International Computer Music Conference, 1986.

- M. Balaban. A Music Workstation Based on Multiple Hierarchical Views of Music. San Francisco, In Proceedings of the 1988 International Computer Music Conference, 1988.

- Alan Belkin. Macintosh Notation Software: Present and Future. Computer Music Journal, 18(1), 1994. Some music notation systems are analysed for ease of use, MIDI handling. The article ends with a plea for a standard notation format. HWN.

- Herbert Bielawa. Review of Sibelius 7. Computer Music Journal, 1993?. A raving review/tutorial of Sibelius 7 for Acorn. (And did they seriously program a RISC chip in ... assembler ?!) HWN.

- Dorothea Blostein and Lippold Haken. Justification of Printed Music. Communications of the ACM, J34(3):88-99, March 1991. This paper provides an overview of the algorithm used in LIME for spacing individual lines. HWN.

- Dorothea Blostein and Lippold Haken. The Lime Music Editor: A Diagram Editor Involving Complex Translations. Software Practice and Experience, 24(3):289–306, march 1994. A description of various conversions, decisions and issues relating to this interactive editor HWN.

- Nabil Bouzaiene, Loïc Le Gall, and Emmanuel Saint-James. Une bibliothèque pour la notation musicale baroque. LNCS. In EP ’98, 1998. Describes ATYS, an extension to Berlioz, that can mimick handwritten baroque style beams.

- Donald Byrd. A System for Music Printing by Computer. Computers and the Humanities, 8:161-72, 1974.

- Donald Byrd. Music Notation by Computer. PhD thesis, Indiana University, 1985. Describes the SMUT (sic) system for automated music printout.

- Donald Byrd. Music Notation Software and Intelligence. Computer Music Journal, 18(1):17–20, 1994. Byrd (author of Nightingale) shows four problematic fragments of notation, and rants about notation programs that try to exhibit intelligent behaviour. HWN.

- Walter B Hewlett and Eleanor Selfridge-Field. Directory of Computer Assisted Research in Musicology. . Annual editions since 1985, many containing surveys of music typesetting technology. SP.

- Alyssa Lamb. The University of Colorado Music Engraving page. 1996. Webpages about engraving (designed with finale users in mind) (sic) HWN.

- Roger B. Dannenberg. Music Representation: Issues, Techniques, and Systems. Computer Music Journal, 17(3), 1993. This article points to some problems and solutions with music representation. HWN.

- Michael Droettboom. Study of music Notation Description Languages. Technical Report, 2000. GUIDO and lilypond compared. LilyPond wins on practical issues as usability and availability of tools, GUIDO wins on implementation simplicity.

- R. F. Ericson. The DARMS Project: A status report. Computing in the humanities, 9(6):291–298, 1975. Gourlay [gourlay86] writes: A discussion of the design and potential uses of the DARMS music-description language.

- H.S. Field-Richards. Cadenza: A Music Description Language. Computer Music Journal, 17(4), 1993. A description through examples of a music entry language. Apparently it has no formal semantics. There is also no implementation of notation convertor. HWN.

- Miguel Filgueiras. Some Music Typesetting Algorithms. .

- Miguel Filgueiras and José Paulo Leal. Representation and manipulation of music documents in SceX. Electronic Publishing, 6(4):507–518, 1993.

- Miguel Filgueiras. Implementing a Symbolic Music Processing System. 1996.

- Eric Foxley. Music — A language for typesetting music scores. Software — Practice and Experience, 17(8):485-502, 1987. A paper on a simple TROFF preprocessor to typeset music.

- Loïc Le Gall. Création d’une police adaptée à la notation musicale baroque. Master’s thesis, École Estienne, 1997.

- Martin Gieseking. Code-basierte Generierung interaktiver Notengraphik. PhD thesis, Universität Osnabrück, 2001.

- David A. Gomberg. A Computer-Oriented System for Music Printing. PhD thesis, Washington University, 1975.

- David A. Gomberg. A Computer-oriented System for Music Printing. Computing and the Humanities, 11:63-80, march 1977. Gourlay [gourlay86] writes: "A discussion of the problems of representing the conventions of musical notation in computer algorithms.".

- John. S. Gourlay. A language for music printing. Communications of the ACM, 29(5):388–401, 1986. This paper describes the MusiCopy musicsetting system and an input language to go with it.

- John S. Gourlay, A. Parrish, D. Roush, F. Sola, and Y. Tien. Computer Formatting of Music. Technical Report OSU-CISRC-2/87-TR3, Department of Computer and Information Science, The Ohio State University, 1987. This paper discusses the development of algorithms for the formatting of musical scores (from abstract). It also appeared at PROTEXT III, Ireland 1986.

- John S. Gourlay. Spacing a Line of Music,. Technical Report OSU-CISRC-10/87-TR35, Department of Computer and Information Science, The Ohio State University, 1987.

- John Grøver. A computer-oriented description of Music Notation. Part III: Accidental Positioning. Technical Report 135, Department of informatics, University of Oslo, 1989. Placement of accidentals crystallised in an enormous set of rules. Same remarks as for [grover89-twovoices] applies.

- John Grøver. A computer-oriented description of Music Notation. Part I. The Symbol Inventory. Technical Report 133, Department of informatics, University of Oslo, 1989. The goal of this series of reports is a full description of music formatting. As these largely depend on parameters of fonts, it starts with a verbose description of music symbols. The subject is treated backwards: from general rules of typesetting the author tries to extract dimensions for characters, whereas the rules of typesetting (in a particular font) follow from the dimensions of the symbols. His symbols do not match (the stringent) constraints formulated by eg. [wanske].

- John Grøver. A computer-oriented description of Music Notation. Part II: Two Voice Sharing a Staff, Leger Line Rules, Dot Positioning. Technical Report 134, Department of informatics, University of Oslo, 1989. A lot rules for what is in the title are formulated. The descriptions are long and verbose. The verbosity shows that formulating specific rules is not the proper way to approach the problem. Instead, the formulated rules should follow from more general rules, similar to [parrish87-simultaneities].

- Lippold Haken and Dorothea Blostein. The Tilia Music Representation: Extensibility, Abstraction, and Notation Contexts for the Lime Music Editor. Computer Music Journal, 17(3):43–58, 1993.

- Lippold Haken and Dorothea Blostein. A New Algorithm for Horizontal Spacing of Printed Music. Banff, In International Computer Music Conference, pages 118-119, Sept 1995. This describes an algorithm which uses springs between adjacent columns.

- Wael A. Hegazy. On the Implementation of the MusiCopy Language Processor,. Technical Report OSU-CISRC-10/87-TR34, Department of Computer and Information Science, The Ohio State University, 1987. Describes the "parser" which converts MusiCopy MDL to MusiCopy Simultaneities and columns. MDL is short for Music Description Language [gourlay86]. It accepts music descriptions that are organised into measures filled with voices, which are filled with notes. The measures can be arranged simultaneously or sequentially. To address the 2-dimensionality, almost all constructs in MDL must be labeled. MDL uses begin/end markers for attribute values and spanners. Rightfully the author concludes that MusiCopy must administrate a "state" variable containing both properties and current spanning symbols. MusiCopy attaches graphic information to the objects constructed in the input: the elements of the input are partially complete graphic objects.

- Wael A. Hegazy and John S. Gourlay. Optimal line breaking in music. Technical Report OSU-CISRC-8/87-TR33, Department of Computer and Information Science, The Ohio State University,, 1987.

- Wael A. Hegazy and John S. Gourlay. (J. C. van Vliet, editor). Optimal line breaking in music. Cambridge University Press, In Proceedings of the International Conference on Electronic Publishing, Document Manipulation and Typography. Nice (France), April 1988.

- Walter B. Hewlett and Eleanor Selfridge-Field, editors. The Virtual Score; representation, retrieval and restoration. Computing in Musicology. MIT Press, 2001.

- H. H. Hoos, K. A. Hamel, K. Renz, and J. Kilian. The GUIDO Music Notation Format—A Novel Approach for Adequately Representing Score-level Music. In Proceedings of International Computer Music Conference, pages 451–454, 1998.

- Peter S. Langston. Unix music tools at Bellcore. Software — Practice and Experience, 20(S1):47–61, 1990. This paper deals with some command-line tools for music editing and playback.

- Dominique Montel. La gravure de la musique, lisibilité esthétique, respect de l’oevre. Lyon, In Musique \& Notations, 1997.

- Giovanni Müller. Interaktive Bearbeitung konventioneller Musiknotation. PhD thesis, Eidgenössische Technische Hochschule Zürich, 1990. This is about engraver-quality typesetting with computers. It accepts the axiom that notation is too difficult to generate automatically. The result is that a notation program should be a WYSIWYG editor that allows one to tweak everything.

- Han Wen Nienhuys and Jan Nieuwenhuizen. LilyPond, a system for automated music engraving. Firenze, In XIV Colloquium on Musical Informatics, pages 167–172, May 2003.

- Cindy Grande. NIFF6a Notation Interchange File Format. Grande Software Inc., 1995. Specs for NIFF, a reasonably comprehensive but binary format for notation HWN.

- Severo M. Ornstein and John Turner Maxwell III. Mockingbird: A Composer’s Amanuensis. Technical Report CSL-83-2, Xerox Palo Alto Research Center, 3333 Coyote Hill Road, Palo Alto, CA, 94304, January 1983.

- Severo M. Ornstein and John Turner Maxwell III. Mockingbird: A Composer’s Amanuensis. Byte, 9, January 1984. A discussion of an interactive and graphical computer system for music composition.

- Stephen Dowland Page. Computer Tools for Music Information Retrieval. PhD thesis, Dissertation University of Oxford, 1988. Don’t ask Stephen for a copy. Write to the Bodleian Library, Oxford, or to the British Library, instead. SP.

- Allen Parish, Wael A. Hegazy, John S. Gourlay, Dean K. Roush, and F. Javier Sola. MusiCopy: An automated Music Formatting System. Technical Report, 1987.

- A. Parrish and John S. Gourlay. Computer Formatting of Musical Simultaneities,. Technical Report OSU-CISRC-10/87-TR28, Department of Computer and Information Science, The Ohio State University, 1987. This note discusses placement of balls, stems, dots which occur at the same moment ("Simultaneity").

- Steven Powell. Music engraving today. Brichtmark, 2002. A "How Steven uses Finale" manual.

- Gary M. Rader. Creating Printed Music Automatically. Computer, 29(6):61–69, June 1996. Describes a system called MusicEase, and explains that it uses "constraints" (which go unexplained) to automatically position various elements.

- Kai Renz. Algorithms and data structures for a music notation system based on GUIDO music notation. PhD thesis, Universität Darmstadt, 2002.

- René Roelofs. Een Geautomatiseerd Systeem voor het Afdrukken van Muziek. Number 45327. Master’s thesis, Erasmus Universiteit Rotterdam, 1991. This dutch thesis describes a monophonic typesetting system, and focuses on the breaking algorithm, which is taken from Hegazy & Gourlay.

- Joseph Rothstein. Review of Passport Designs’ Encore Music Notation Software. Computer Music Journal, ?.

- Dean K. Roush. Using MusiCopy. Technical Report OSU-CISRC-18/87-TR31, Department of Computer and Information Science, The Ohio State University, 1987. User manual of MusiCopy.

- D. Roush. Music Formatting Guidelines. Technical Report OSU-CISRC-3/88-TR10, Department of Computer and Information Science, The Ohio State University, 1988. Rules on formatting music formulated for use in computers. Mainly distilled from [Ross] HWN.

- Eleanor Selfridge-Field, editor. Beyond MIDI: the handbook of musical codes. MIT Press, 1997. A description of various music interchange formats.

- Donald Sloan. Aspects of Music Representation in HyTime/SMDL. Computer Music Journal, 17(4), 1993. An introduction into HyTime and its score description variant SMDL. With a short example that is quite lengthy in SMDL.

- International Organization for Standardization~(ISO). Information Technology - Document Description and Processing Languages - Standard Music Description Language (SMDL). Number ISO/IEC DIS 10743. 1992.

- Leland Smith. Editing and Printing Music by Computer, volume 17. 1973. Gourlay [gourlay86] writes: A discussion of Smith’s music-printing system SCORE.

- F. Sola. Computer Design of Musical Slurs, Ties and Phrase Marks,. Technical Report OSU-CISRC-10/87-TR32, Department of Computer and Information Science, The Ohio State University, 1987. Overview of a procedure for generating slurs.

- F. Sola and D. Roush. Design of Musical Beams,. Technical Report OSU-CISRC-10/87-TR30, Department of Computer and Information Science, The Ohio State University, 1987. Calculating beam slopes HWN.

- Howard Wright. how to read and write tab: a guide to tab notation. . FAQ (with answers) about TAB, the ASCII variant of Tablature. HWN.

- Geraint Wiggins, Eduardo Miranda, Alaaaan Smaill, and Mitch Harris. A Framework for the evaluation of music representation systems. Computer Music Journal, 17(3), 1993. A categorisation of music representation systems (languages, OO systems etc) split into high level and low level expressiveness. The discussion of Charm and parallel processing for music representation is rather vague. HWN.

Notensatz-Bibliographie

- Harald Banter. Akkord Lexikon. Schott’s Söhne, Mainz, Germany, 1987. Comprehensive overview of commonly used chords. Suggests (and uses) a unification for all different kinds of chord names.

- A Barksdale. The Printed Note: 500 Years of Music Printing and Engraving. The Toledo Museum of Art, Toledo, Ohio, January 1957. ‘The exhibition "The Printed Note" attempts to show the various processes used since the second of the 15th century for reproducing music mechanically ... ’. The illustration mostly feature ancient music.

- Laszlo Boehm. Modern Music Notation. G. Schirmer, Inc., New York, 1961. Heussenstamm writes: A handy compact reference book in basic notation.

- H. Elliot Button. System in Musical Notation. Novello and co., London, 1920.

- Herbert Chlapik. Die Praxis des Notengraphikers. Doblinger, 1987. An clearly written book for the casually interested reader. It shows some of the conventions and difficulties in printing music HWN.

- Anthony Donato. Preparing Music Manuscript. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ, 1963.

- Donemus. Uitgeven van muziek. Donemus Amsterdam, 1982. Manual on copying for composers and copyists at the Dutch publishing house Donemus. Besides general comments on copying, it also contains a lot of hands-on advice for making performance material for modern pieces.

- William Gamble. Music Engraving and printing. Historical and Technical Treatise. Sir Isaac Pitman & Sons, ltd., 1923. This patriotic book was an attempt to promote and help British music engravers. It is somewhat similar to Hader’s book [hader48] in scope and style, but Gamble focuses more on technical details (Which French punch cutters are worth buying from, etc.), and does not treat typographical details, such as optical illusions. It is available as reprint from Da Capo Press, New York (1971).

- Tom Gerou and Linda Lusk. Essential Dictionary of Music Notation. Alfred Publishing, Van Nuys CA, 1996. A cheap, concise, alphabetically ordered list of typesetting and music (notation) issues with a rather simplistic attitude but in most cases "good-enough" answers JCN.

- Elaine Gould. Behind Bars. Faber Music Ltd., 2011. A comprehensive guide to the rules and conventions of music notation. Covering everything from basic themes to complex techniques and providing a comprehensive grounding in notational principles.

- Elaine Gould. Hals über Kopf. Edition Peters, 2014. Ein vollständiges Regelwerk für den Modernen Notensatz auf höchstem Niveau, ein Meilenstein der Notationskunde und ein Leitfaden für jeden Musiker, der sich auf diesem Gebiet umfassende Kenntnisse aneignen möchte.

- Karl Hader. Aus der Werkstatt eines Notenstechers. Waldheim–Eberle Verlag, Vienna, 1948. Hader was a chief-engraver in a Viennese engraving workshop. This beautiful booklet was intended as an introduction for laymen on the art of engraving. It contains a step by step, in-depth explanation of how to cut and stamp music into zinc plates. It also contains a few compactly formulated rules on musical orthography. Out of print.

- George Heussenstamm. The Norton Manual of Music Notation. Norton, New York, 1987. Hands-on instruction book for copying (ie. handwriting) music. Fairly complete. HWN.

- Klaus Ignatzek. Die Jazzmethode für Klavier 1. Schott, 1995. This book contains a system for denoting chords that is used in LilyPond.

- Andreas Jaschinski, editor. Notation. Number BVK1625. Bärenreiter Verlag, 2000.

- Harold Johnson. How to write music manuscript. Carl Fischer, Inc., New York, 1946.

- Erdhard Karkoshka. Notation in New Music; a critical guide to interpretation and realisation. Praeger Publishers, New York, 1972. (Out of print).

- Mark Mc Grain. Music notation. Hal Leonard Publishing Corporation, 1991. HWN writes: ‘Book’ edition of lecture notes from XXX school of music. The book looks like it is xeroxed from bad printouts. The content has nothing you won’t find in other books like [read] or [heussenstamm].

- mpa. Standard music notation specifications for computer programming.. MPA, December 1996. Pamphlet explaining a few fine points in music font design HWN.

- Richard Rastall. The Notation of Western Music: an Introduction. J. M. Dent \& Sons London, 1983. Interesting account of the evolution and origin of common notation starting from neumes, and ending with modern innovations HWN.

- Gardner Read. Modern Rhythmic Notation. Indiana University Press, 1978. Sound (boring) review of the various hairy rhythmic notations used by avant-garde composers HWN.

- Gardner Read. Music Notation: a Manual of Modern Practice. Taplinger Publishing, New York, 1979. This is as close to the “standard” reference work for music notation issues as one is likely to get.

- Clinton Roemer. The Art of Music Copying. Roerick music co., Sherman Oaks (CA), 2nd edition, 1984. Out of print. Heussenstamm writes: an instructional manual which specializes in methods used in the commercial field.

- Glen Rosecrans. Music Notation Primer. Passantino, New York, 1979. Heussenstamm writes: Limited in scope, similar to [Roemer84].

- Carl A Rosenthal. A Practical Guide to Music Notation. MCA Music, New York, 1967. Heussenstamm writes: Informative in terms of traditional notation. Does not concern score preparation.

- Ted Ross. Teach yourself the art of music engraving and processing. Hansen House, Miami, Florida, 1987.

- Schirmer. The G. Schirmer Manual of Style and Usage. The G. Schirmer Publications Department, New York, 2001. This is the style guide for Schirmer publications. This manual specifically focuses on preparing print for publication by Schirmer. It discusses many details that are not in other, normal notation books. It also gives a good idea of what is necessary to bring printouts to publication quality. It can be ordered from the rental department.

- Kurt Stone. Music Notation in the Twentieth Century. Norton, New York, 1980. Heussenstamm writes: The most important book on notation in recent years.

- Börje Tyboni. Noter Handbok I Traditionell Notering. Gehrmans Musikförlag, Stockholm, 1994. Swedish book on music notation.

- Albert C. Vinci. Fundamentals of Traditional Music Notation. Kent State University Press, 1989.

- Helene Wanske. Musiknotation — Von der Syntax des Notenstichs zum EDV-gesteuerten Notensatz. Schott-Verlag, Mainz, 1988.

- Maxwell Weaner and Walter Boelke. Standard Music Notation Practice. Music Publisher’s Association of the United States Inc, New York, 1993.

- Johannes Wolf. Handbuch der Notationskunde. Breitkopf & Hartel, Leipzig, 1919. Very thorough treatment (in two volumes) of the history of music notation.

| [ << Literatur ] | [Top][Contents][Index] | [ LilyPond-Index >> ] |

| [ < Lange Literaturliste ] | [ Up : Top ] | [ LilyPond-Index > ] |

Appendix A GNU Free Documentation License

Copyright © 2000, 2001, 2002, 2007, 2008 Free Software Foundation, Inc. https://fsf.org/ Everyone is permitted to copy and distribute verbatim copies of this license document, but changing it is not allowed.

- PREAMBLE

The purpose of this License is to make a manual, textbook, or other functional and useful document free in the sense of freedom: to assure everyone the effective freedom to copy and redistribute it, with or without modifying it, either commercially or noncommercially. Secondarily, this License preserves for the author and publisher a way to get credit for their work, while not being considered responsible for modifications made by others.

This License is a kind of “copyleft”, which means that derivative works of the document must themselves be free in the same sense. It complements the GNU General Public License, which is a copyleft license designed for free software.

We have designed this License in order to use it for manuals for free software, because free software needs free documentation: a free program should come with manuals providing the same freedoms that the software does. But this License is not limited to software manuals; it can be used for any textual work, regardless of subject matter or whether it is published as a printed book. We recommend this License principally for works whose purpose is instruction or reference.

- APPLICABILITY AND DEFINITIONS

This License applies to any manual or other work, in any medium, that contains a notice placed by the copyright holder saying it can be distributed under the terms of this License. Such a notice grants a world-wide, royalty-free license, unlimited in duration, to use that work under the conditions stated herein. The “Document”, below, refers to any such manual or work. Any member of the public is a licensee, and is addressed as “you”. You accept the license if you copy, modify or distribute the work in a way requiring permission under copyright law.

A “Modified Version” of the Document means any work containing the Document or a portion of it, either copied verbatim, or with modifications and/or translated into another language.

A “Secondary Section” is a named appendix or a front-matter section of the Document that deals exclusively with the relationship of the publishers or authors of the Document to the Document’s overall subject (or to related matters) and contains nothing that could fall directly within that overall subject. (Thus, if the Document is in part a textbook of mathematics, a Secondary Section may not explain any mathematics.) The relationship could be a matter of historical connection with the subject or with related matters, or of legal, commercial, philosophical, ethical or political position regarding them.

The “Invariant Sections” are certain Secondary Sections whose titles are designated, as being those of Invariant Sections, in the notice that says that the Document is released under this License. If a section does not fit the above definition of Secondary then it is not allowed to be designated as Invariant. The Document may contain zero Invariant Sections. If the Document does not identify any Invariant Sections then there are none.

The “Cover Texts” are certain short passages of text that are listed, as Front-Cover Texts or Back-Cover Texts, in the notice that says that the Document is released under this License. A Front-Cover Text may be at most 5 words, and a Back-Cover Text may be at most 25 words.

A “Transparent” copy of the Document means a machine-readable copy, represented in a format whose specification is available to the general public, that is suitable for revising the document straightforwardly with generic text editors or (for images composed of pixels) generic paint programs or (for drawings) some widely available drawing editor, and that is suitable for input to text formatters or for automatic translation to a variety of formats suitable for input to text formatters. A copy made in an otherwise Transparent file format whose markup, or absence of markup, has been arranged to thwart or discourage subsequent modification by readers is not Transparent. An image format is not Transparent if used for any substantial amount of text. A copy that is not “Transparent” is called “Opaque”.

Examples of suitable formats for Transparent copies include plain ASCII without markup, Texinfo input format, LaTeX input format, SGML or XML using a publicly available DTD, and standard-conforming simple HTML, PostScript or PDF designed for human modification. Examples of transparent image formats include PNG, XCF and JPG. Opaque formats include proprietary formats that can be read and edited only by proprietary word processors, SGML or XML for which the DTD and/or processing tools are not generally available, and the machine-generated HTML, PostScript or PDF produced by some word processors for output purposes only.

The “Title Page” means, for a printed book, the title page itself, plus such following pages as are needed to hold, legibly, the material this License requires to appear in the title page. For works in formats which do not have any title page as such, “Title Page” means the text near the most prominent appearance of the work’s title, preceding the beginning of the body of the text.

The “publisher” means any person or entity that distributes copies of the Document to the public.

A section “Entitled XYZ” means a named subunit of the Document whose title either is precisely XYZ or contains XYZ in parentheses following text that translates XYZ in another language. (Here XYZ stands for a specific section name mentioned below, such as “Acknowledgements”, “Dedications”, “Endorsements”, or “History”.) To “Preserve the Title” of such a section when you modify the Document means that it remains a section “Entitled XYZ” according to this definition.

The Document may include Warranty Disclaimers next to the notice which states that this License applies to the Document. These Warranty Disclaimers are considered to be included by reference in this License, but only as regards disclaiming warranties: any other implication that these Warranty Disclaimers may have is void and has no effect on the meaning of this License.

- VERBATIM COPYING

You may copy and distribute the Document in any medium, either commercially or noncommercially, provided that this License, the copyright notices, and the license notice saying this License applies to the Document are reproduced in all copies, and that you add no other conditions whatsoever to those of this License. You may not use technical measures to obstruct or control the reading or further copying of the copies you make or distribute. However, you may accept compensation in exchange for copies. If you distribute a large enough number of copies you must also follow the conditions in section 3.

You may also lend copies, under the same conditions stated above, and you may publicly display copies.

- COPYING IN QUANTITY

If you publish printed copies (or copies in media that commonly have printed covers) of the Document, numbering more than 100, and the Document’s license notice requires Cover Texts, you must enclose the copies in covers that carry, clearly and legibly, all these Cover Texts: Front-Cover Texts on the front cover, and Back-Cover Texts on the back cover. Both covers must also clearly and legibly identify you as the publisher of these copies. The front cover must present the full title with all words of the title equally prominent and visible. You may add other material on the covers in addition. Copying with changes limited to the covers, as long as they preserve the title of the Document and satisfy these conditions, can be treated as verbatim copying in other respects.

If the required texts for either cover are too voluminous to fit legibly, you should put the first ones listed (as many as fit reasonably) on the actual cover, and continue the rest onto adjacent pages.

If you publish or distribute Opaque copies of the Document numbering more than 100, you must either include a machine-readable Transparent copy along with each Opaque copy, or state in or with each Opaque copy a computer-network location from which the general network-using public has access to download using public-standard network protocols a complete Transparent copy of the Document, free of added material. If you use the latter option, you must take reasonably prudent steps, when you begin distribution of Opaque copies in quantity, to ensure that this Transparent copy will remain thus accessible at the stated location until at least one year after the last time you distribute an Opaque copy (directly or through your agents or retailers) of that edition to the public.

It is requested, but not required, that you contact the authors of the Document well before redistributing any large number of copies, to give them a chance to provide you with an updated version of the Document.

- MODIFICATIONS

You may copy and distribute a Modified Version of the Document under the conditions of sections 2 and 3 above, provided that you release the Modified Version under precisely this License, with the Modified Version filling the role of the Document, thus licensing distribution and modification of the Modified Version to whoever possesses a copy of it. In addition, you must do these things in the Modified Version:

- Use in the Title Page (and on the covers, if any) a title distinct from that of the Document, and from those of previous versions (which should, if there were any, be listed in the History section of the Document). You may use the same title as a previous version if the original publisher of that version gives permission.

- List on the Title Page, as authors, one or more persons or entities responsible for authorship of the modifications in the Modified Version, together with at least five of the principal authors of the Document (all of its principal authors, if it has fewer than five), unless they release you from this requirement.

- State on the Title page the name of the publisher of the Modified Version, as the publisher.

- Preserve all the copyright notices of the Document.

- Add an appropriate copyright notice for your modifications adjacent to the other copyright notices.

- Include, immediately after the copyright notices, a license notice giving the public permission to use the Modified Version under the terms of this License, in the form shown in the Addendum below.

- Preserve in that license notice the full lists of Invariant Sections and required Cover Texts given in the Document’s license notice.

- Include an unaltered copy of this License.